the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Algorithms for optimization of branching gravity-driven water networks

Ian Dardani

Gerard F. Jones

The design of a water network involves the selection of pipe diameters that satisfy pressure and flow requirements while considering cost. A variety of design approaches can be used to optimize for hydraulic performance or reduce costs. To help designers select an appropriate approach in the context of gravity-driven water networks (GDWNs), this work assesses three cost-minimization algorithms on six moderate-scale GDWN test cases. Two algorithms, a backtracking algorithm and a genetic algorithm, use a set of discrete pipe diameters, while a new calculus-based algorithm produces a continuous-diameter solution which is mapped onto a discrete-diameter set. The backtracking algorithm finds the global optimum for all but the largest of cases tested, for which its long runtime makes it an infeasible option. The calculus-based algorithm's discrete-diameter solution produced slightly higher-cost results but was more scalable to larger network cases. Furthermore, the new calculus-based algorithm's continuous-diameter and mapped solutions provided lower and upper bounds, respectively, on the discrete-diameter global optimum cost, where the mapped solutions were typically within one diameter size of the global optimum. The genetic algorithm produced solutions even closer to the global optimum with consistently short run times, although slightly higher solution costs were seen for the larger network cases tested. The results of this study highlight the advantages and weaknesses of each GDWN design method including closeness to the global optimum, the ability to prune the solution space of infeasible and suboptimal candidates without missing the global optimum, and algorithm run time. We also extend an existing closed-form model of Jones (2011) to include minor losses and a more comprehensive two-part cost model, which realistically applies to pipe sizes that span a broad range typical of GDWNs of interest in this work, and for smooth and commercial steel roughness values.

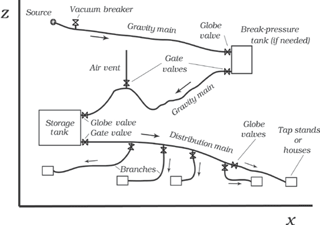

A gravity-driven water network (GDWN) is commonly used to deliver potable water from a source at a high elevation, such as a natural spring or reservoir, to households or public tap stands (Fig. 1). When feasible, gravity-driven water networks are attractive in comparison to pumped networks because of their simplicity and lower capital, operational, and maintenance costs. In addition, in many locations where GDWN are considered, there may be little or no access to reliable grid-based electrical power for pumps. To improve reliability, networks may be designed with loops or multiple water sources, although often material cost considerations restrict attention to single-source branched networks.

Water networks are modeled as a collection of nodes, each representing a point of water demand or supply, which are connected with links representing pipes. The geometrical layout of the site is known and fixed, including water source and demand locations and elevations of all nodes. For the present work, design flow rates are determined from community survey data, which are extrapolated for future population growth. Networks in this category are referred to as “demand-driven” designs. Bhave (1978, 1983) refers to these as “Q-specified” designs. Thus, to design a network of this type, pipe diameters for each link must be chosen such that acceptable but arbitrary minimum (positive) pressure heads are maintained at each node given the design flow rate at the node. Furthermore, application of the energy equation to each link in the network demonstrates that the design problem is nonunique; i.e., choosing different pressure heads at the nodes will result in a different pipe diameter solution for the network, and thus different network costs. Minimizing network cost will produce a unique solution to the design problem, i.e., unique link diameters and nodal pressure heads.

In practice, gravity-driven water networks are commonly designed by a marching method, where diameters for each link of the network are chosen sequentially. After selecting a reasonable diameter for each link, the designer calculates the pressure head at the link outlet, and proceeds to the next link if this result is acceptable. In this way, the designer marches through the network until all pipe diameters have been selected. This method produces a feasible solution, but not a cost optimized one. As noted by Bhave (2003), cost savings of 20–30 % can result from the use of optimization techniques. In developing regions, the cost of a water network can be prohibitive, adding to the importance of optimizing network design.

Within the provided framework, the global optimum can be found through an exhaustive search of the solution space, known as complete enumeration, although this is infeasible when considering networks with many links and diameter choices (Kadu et al., 2008; González-Cebollada et al., 2011). To reduce the computational time required by enumeration, authors have proposed various partial enumeration methods which prune the search space (Kadu et al., 2008), although some of these techniques may remove the global optimum (Simpson et al., 1994). The most common types of algorithms that have been applied to optimize water network design include traditional deterministic methods, heuristic methods, metaheuristic methods, multi-objective methods, and decomposition methods (Zhao et al., 2016).

Deterministic methods include linear programming (LP), dynamic programming, and nonlinear programming (NLP), and typically involve rigorous mathematical approaches (Zhao et al., 2016). A brief overview and comparison of these algorithms is given in Kansal et al. (1996), who use a single-part cost correlation for metric pipe diameters between 100 and 350 mm. Linear programming techniques have relatively low computational complexity and allow each link to be composed of two diameters, called a split-pipe solution, although these may not always be practical to implement (Bhave, 1983; Kessler and Shamir, 1989; Swamee and Sharma, 2000; Samani and Mottaghi, 2006). LP can also get stuck in a local optimum (Zhao et al., 2016), although combining LP with metaheuristic techniques can help with the problem's non-smoothness properties (Krapivka and Ostfeld, 2009). Dynamic programming has been used by Yang et al. (1975) and Martin (1980) to optimize networks in stages. This approach begins at the discharge nodes, proceeding to select feasible diameters and joints for upstream stages and storing these partial candidates in memory until the source node is reached. At this point, the algorithm reviews the feasible segment design options and selects a combination of stage solutions producing the lowest cost overall solution. This method, however, requires the designer to allow a relatively narrow range for the design pressure of each node, or otherwise store a large set of feasible candidate solutions in memory and also allow adjoining branches to arrive at different heads at the same node.

Nonlinear programming, a calculus-based method, deals with each link's diameter as a continuous variable. Using Lagrange multipliers and a one-part, pipe-cost model with minor-lossless flow, Swamee and Sharma (2000) developed systems of equations for both continuous and discrete pipe diameters for branch networks, assuming a constant friction factor. When solved, the solution gives diameter values that minimize distribution main cost, not network cost. In carrying out the solution, iteration is required to update the value of the friction factor. For the discrete diameter case, large computational times were noted by Swamee and Sharma because of the stiffness of the mathematical system. Cases where one or more nodal pressure heads are not acceptable need to be treated manually by the designer in various ways as discussed by the authors. For branching networks, Jones (2011) showed that by restricting the focus to smooth-turbulent (turbulent flow in a smooth pipe) minor-lossless flow, and the use of a one-part, pipe-cost model, a simple nonlinear algebraic equation for each internal node in the distribution main could be developed. The development of this algorithm, as well as solution methodology, differs from that of Bhave (1978), which assumes constancy in several terms and thus requires iteration to solve. The Jones algorithm has been extended in the present work to include minor losses and rough pipe. When solved simultaneously with the energy equation for each link, a unique solution for all link diameters and nodal pressure head values is obtained which produces minimum network cost, as opposed to the distribution main cost as in Swamee and Sharma (2000). The method of Jones also applies to serial and loop networks because of its generality.

Heuristic methods follow specific rules to incrementally build better solutions, although the rules are not strictly formulated to trend towards local or global optima. An approach by Monbaliu et al. (1990) sets all network pipes to their minimum size, where the pipe that has a maximum head loss gradient is incremented to its next-highest size until all nodal head requirements are satisfied. Similarly, an algorithm by Keedwell and Khu (2006) selects an initial solution and iteratively responds to nodal head deficits and surpluses by incrementing or decrementing pipe sizes accordingly until a feasible solution is found. Suribabu (2012) proposed a heuristic that identifies pipes to increment or decrement in size based on flow velocity and alternative metrics such as proximity to the source node, achieving acceptable cost results with computational efficiency. While these algorithms are typically computationally efficient, they do not guarantee a global optimum.

Metaheuristic optimization methods allow for a set of solutions to evolve through random processes that are guided with an objective function which rewards low network costs and penalizes hydraulic insufficiencies. Examples include evolutionary algorithms, which are most commonly genetic algorithms (Krapivka and Ostfeld, 2009; Simpson et al., 1994; Kadu et al., 2008; Prasad and Park, 2004), simulated annealing (Vasan and Simonovic, 2010; Tospornsampan et al., 2007), ant colony optimization (Maier et al., 2003), and differential evolution (Vasan and Simonovic, 2010). As reviewed by Nicklow et al. (2010), evolutionary algorithms are an emerging popular alternative to the deterministic methods, and they offer the opportunity to accommodate unique constraints and multiple design objectives. The main challenges for evolutionary algorithms are the difficulty of incorporating constraints into objective functions, the optimum selection of parameters, and a relatively large amount of computational effort. In addition to optimizing for cost, multi-objective methods, often based on evolutionary algorithms, allow the designer to choose from a Pareto optimal front of objectives, such as cost and reliability (Prasad and Park, 2004). In addition to water network design, metaheuristic algorithms have been used for a range of problems in water resources engineering, such as rainfall and runoff modeling (Taormina and Chau, 2015).

Decomposition methods involve the partitioning of networks into smaller sub-networks which are each optimized using one of many types of techniques and then combined into an overall solution. In some cases, the loops in the sub-networks are removed, producing branching trees which are then optimized individually. Techniques used to optimize the sub-networks can involve multiple methods, including linear programming (Saldarriaga et al., 2013) and differential evolution (Zheng et al., 2013), with a later stage optimizing the network as a whole using the sub-network solutions as inputs. Note that another distinct use of the term “decomposition” refers to the approach of iteratively solving “inner” and “outer” mathematical problem formulations, and has been used in the literature by Krapivka and Ostfeld (2009) who traces its use in this context back to Alperovits and Shamir (1977).

In the present study, we present three algorithms, each from one of three major categories of methods applied to the cost optimization of water distribution networks, and compare their performance on five cases adapted from real GDWNs. These algorithms include (1) the calculus-based (CB) optimization model of Jones (2011), an NLP method; (2) backtracking (BT), a partial enumeration method; and (3) a genetic algorithm (GA), a metaheuristic method. Major distinguishing features of these algorithms include their working use of continuous diameters (CB) versus discrete diameters (BT and GA), their deterministic (CB and BT) versus stochastic (GA) search process, and their relative scalability as better (CB, GA) and worse (BT) for larger networks. In terms of their ability to find a global optimum solution for the problem formulation, CB finds a global optimum for continuous diameters but cannot guarantee a discrete diameter global optimum in its mapped solution, BT can guarantee a discrete global optimum, and GA cannot guarantee an optimum. For a direct comparison of techniques, the pipe costs used for all algorithms are found by interpolating a two-part cost formula based on a curve fit of real cost data for available diameter values. The three algorithms are tested against networks adapted from field data on five actual GDWNs installed in Panama, Nicaragua, and the Philippines.

Within the broader context of water network problem formulations, this paper is concerned with finding cost-optimal single-diameter solutions to branching water distribution networks with steady-state demand flows and pre-specified pipe locations. By implication of being gravity-driven, the problem does not involve the use of pumping stations. This problem formulation is directly applicable to typical gravity-driven water networks, and is also useful for multi-objective algorithms, the consideration of sub-networks in a decomposition technique, pumped networks, and looped system optimization, which can involve reformulating the problem into a branching configuration.

The results of this study highlight the advantages and weaknesses of each GDWN design method including closeness to the global optimum, the ability to prune the solution space of infeasible and suboptimal candidates without missing the global optimum, and also computational time. We present two pre-processors which discrete-diameter search methods can use to reduce the search space without pruning the global optimum. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first implementation of “pre-processor 1” in enumeration methods and the first implementation of “pre-processor 2” in any water network design method. We also extend the Jones closed-form model to include minor losses, a more comprehensive two-part cost model, which realistically applies to pipe sizes that span a broad range typical of GDWNs of interest in this work, and for smooth and commercial steel roughness values.

Branching networks are considered (Fig. 1), where all branches connect a distribution main node with a delivery node, shown as tap stands or houses. For each link in a network of NL links, pipe length (L) and the net elevation change (Δz) are considered known and fixed. Steady-state flow rates (Q) are prescribed for each link based on the demand flow data at delivery nodes. As noted above, demand flows are determined by community surveys and extrapolated in time to quantitatively account for population growth. Minor losses are accounted for through a minor loss coefficient K or a dimensionless equivalent pipe length, (Le∕D, or in symbol form, LebyD), where Le is the pipe length of diameter D whose frictional loss results in the corresponding minor loss. An optimal solution is obtained by selecting pipe diameters (D) from a set of commercially available diameters such that the network's material cost is minimized. With ND choices of diameters for NL links, the problem has candidate solutions.

For all nodes, pressure head, h, is greater than or equal to a chosen minimum, hmin. The value for hmin is selected to eliminate possible leakage of contaminated ground water into the network should the operating conditions change in an unanticipated way. The change in pressure head, Δh, across each link is calculated with the energy equation for pipe flow as follows:

where for each link, α is the kinetic energy correction factor and f is the Darcy friction factor, calculated with the Colebrook–White equation (Colebrook and White, 1937) or Churchill correlation (Churchill, 1977), and g is acceleration of gravity. The kinetic energy correction factor, α, is considered only in the first link, where acceleration from a zero-velocity source is sometimes non-negligible for the smallest of GDWNs that have been encountered. Thus,

where Re is the Reynolds number for pipe flow, 4Q∕πνD, and ν is the kinematic viscosity of water. The possibility of laminar flow (Re≤2300) is permitted since branches from the smallest GDWN observed in practice have been in this regime.

The pressure upper bound is not incorporated into the optimization process. Worst-case pressure conditions occur under hydrostatic conditions, which are directly related to the maximum elevation change in the network and where no flow occurs. Therefore, before the optimization process is undertaken, the selections of appropriate pressure ratings for the pipe and, if needed, break-pressure tanks are left to the correct judgment of the designer under no-flow conditions. In addition, precautions against water hammer are left to the designer.

In this section we develop a new calculus-based algorithm for pipe diameters that minimize overall pipe cost for the network. First appearing in Jones (2011), this algorithm is solved simultaneously with the energy equation for each link to produce unique solutions for D and nodal pressure head values that minimize network pipe cost, as opposed to only the distribution main cost as in Swamee and Sharma (2000). The method also applies to serial and loop networks but the focus for the present work is on branching networks.

We assume continuous pipe diameters in this section; values that result from the solution of the energy equation. Mapping between continuous diameters and the discrete nominal sizes, required to complete the design, will be addressed below.

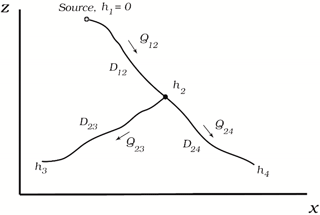

Consider the three-pipe network shown in Fig. 2. Pipes 1–2, 2–3, and 2–4 meet where head h2 is unknown. Each pipe has a prescribed volume flow rate and length and unknown diameter D as shown. The change in elevation between the top and bottom of each pipe is Δz, and Δh is the change in pressure head. There is a prescribed head at each outlet for pipes 2–3 and 2–4.

To facilitate insight, we at first assume turbulent flow (which can be verified post-calculation if necessary) in smooth pipe and that minor losses are negligible. Two sources for the friction factor for smooth-turbulent flow are considered, namely the classical Blasius equation (reported in Streeter et al., 1998), , and the Swamee–Jain correlation (Swamee and Jain, 1976), (though not explicitly appearing in this reference, f from the Swamee–Jain correlation is obtained by writing it for smooth pipe and comparing this with the energy equation, where f is assumed to be in the form aRen). The Blasius equation has higher accuracy (2 % for low Re and 3 % for high Re) in the range 104 < Re < 105, over which most of the GDWNs in this work operate, compared with the Swamee–Jain correlation of +8 %/−3 %, thus the Blasius equation is chosen for this work. A combination of the Blasius equation with the energy equation gives explicit formulas for D for the three links in Fig. 2. For simplicity, and to reduce the number of free parameters, the conditions for pipes 2–3 and 2–4 are assumed to be identical without loss of generality. We therefore obtain

With our assumptions and inspection of Fig. 2, and , we furthermore obtain

The single-part pipe-cost model can be assumed to follow a power-law relationship (Swamee and Sharma, 2008)

where C is cost per unit length of pipe, a is a constant coefficient, b is a constant exponent, and Du an assumed unit diameter. A more robust, two-part model, valid for a greater range of pipe sizes than that of Swamee and Sharma (2008), will be used below. The use of pipe material cost as the objective function was assumed because of relevance. In most GDWNs of interest in this work, installation labor comes from the local community and has no well-defined associated cost, such that the material cost for the network is of prime importance. For a more general case, the economics of a GDWN may be more encompassing and include materials, labor, operation and maintenance, depreciation, taxes, and salvage, among others. The time value of money may also need to be considered, which includes interest rates and estimation of the network lifetime.

With Eq. (4) the general expression for the total cost for the pipe material, CT, is obtained by summing over all links ij,

which, for the present problem, becomes

The mathematical basis for a unique solution for h2 with cost minimization is now presented. In addition to the fixed pipe lengths, the total cost depends on the diameters for all pipes in the network. For the case of Fig. 2, where we now allow pipe 2–3 and pipe 2–4 to be different, we get

Using the chain rule from the calculus, the total differential of Eq. (7) is

The minimum value of CT is found once dCT=0 (and once it is verified that the second derivative of CT is positive thus indicating that CT is indeed a minimum). Requiring this, we obtain

The cost CT is from Eq. (5), so the derivatives like in Eq. (9) are written in general as

for any link ij.

The derivatives like in Eq. (9) are obtained by taking the partial derivative of the pipe diameter with respect to the relevant pressure head in the appropriate energy equation. For the full energy equation, where D appears in a nonlinear way in more than one location, this would be done using numerical methods. However, if we assume minor-lossless, smooth-turbulent flow as noted above, we can use the energy equations like Eq. (3). We therefore obtain the following for pipe 1–2:

for pipe 2–3, we get

and for pipe 2–4,

Equations (10)–(13) are combined with Eq. (9) to produce a single algebraic equation that depends on h2, as well as D12, D23, and D24. Introducing D12,D23, and D24 from Eq. (3) into this algebraic equation, we get

The general form of Eq. (14), written at any internal node is

where the hydraulic gradient, Sij, is

In Eq. (15) the indices ij,in and ij,out on the summations refer to inflows and outflows at the node (e.g., in Fig. 2, ij,in = 12 and ij,out = 23 and 24). Equation (15), the new CB algorithm proposed in this work, is written for each internal node in the network and solved simultaneously with the energy equation for each link to obtain unique and optimal values of Dij for all links and hj for all internal nodes. It is understood that the nodal pressure heads determined from the solution of this system must be greater than or equal to the hmin prescribed for the network. For nodes that do not satisfy this condition, the pressure head is set equal to hmin, as part of the CB algorithm. Thus, .

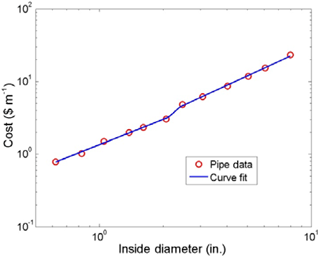

Minor losses using the equivalent-length method can be included in the above developments by artificially extending the length of the link by Le in which minor loss occurs, thus contributing a non-zero LebyD term in Eq. (1). We also extend the cost model of Eq. (5) from Swamee and Sharma (2008) to encompass two different ranges of pipe diameters having two different coefficients a and exponents b. The link between the two ranges starts at discrete pipe size Dco, at and below which the cost model for the small (subscript s) pipe sizes applies, and discrete pipe size Dco+1, at and above which the cost model for the large (subscript l) pipe sizes applies. The cutoff diameter, Dco is chosen by the designer based on inspection of cost vs. diameter data. Thus,

In Eq. (17), as and al are the coefficients for the small (designated by subscript s) and large (subscript l) pipe size regions, respectively, and bs and bl are the exponents for the small and large pipe size regions, respectively. A cubic spline is fit between pipe sizes Dco and Dco+1 to complete the transition between small and large pipe sizes. The coefficients of this polynomial are c1, c2, c3, and c4 as seen in Eq. (17). These coefficients are evaluated by matching the cubic polynomial and pipe data at Dco and Dco+1 and the first derivative of the polynomial with respect to Dij∕Du to at Dij=Dco and to at . An example of data for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe and the curve fit is shown in Fig. 3. The results of the curve fit are as follows: Dco=2.067 in., in., as = USD 1.349 m−1, bs=1.157, al = USD 1.381 m−1, bl=1.344, c1 = USD 237.516 m−1, c2 = USD 316.125 m−1, c3 = USD 140.450 m−1, c4 = −USD 20.499 m−1. It is clear from inspection of Fig. 3 that a one-part cost model would not have produced an acceptable curve-fit to pipe-cost data.

With the inclusion of the two-part cost model and minor loss term, Eq. (15) becomes

where B=0.1989 and

and A accounts for the effect of pipe roughness (smooth and commercial steel). The term is the derivative of the cost function per unit length with respect to D∕Du. For the two-part cost model from above, we obtain

Equation (18), and its simpler form Eq. (15) for minor-lossless flow and a single-part pipe-cost model (it is easy to show that Eq. (18) regresses to Eq. (15) for these conditions), is the root of the calculus-based optimization in this work and is applied at all internal nodes to uniquely determine hj. Equation (18) is valid over the range of ∼ 4000 < Re < ∼ 300 000. Algorithms to solve a general set of independent, nonlinear algebraic equations using, for example, the Levenberg–Marquardt, quasi-Newton, Newton–Raphson, or conjugate gradient methods are available in most commercial math packages including Matlab (1 Apple Hill Drive, Natick, MA USA 01760) and Mathcad (http://www.ptc.com 31 January 2018). We used the package Mathcad in the present work. Thus, compared with an iterative solution procedure, a solution flowchart is not relevant here.

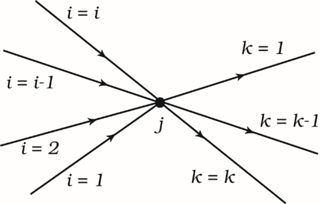

Bhave (1978) first proposed an algorithm like Eq. (15) using slightly different notation than here. For clarity, we re-present Eq. (15) using Bhave's notation as

where the ij and jk notation are shown in Fig. 4. Index j spans all internal nodes along the distribution main. A quantitative comparison between Eq. (18) and the method of Bhave is presented below.

Backtracking (BT) and genetic algorithm (GA) assess candidate solutions composed of discrete diameters from a commercially available set. These candidates are represented by a vector of NL elements where each element corresponds to a commercially available diameter of a network link. To reduce the computational time associated with these evaluations, the constraints imposed by the energy equation and cost minimization may be more efficiently evaluated through lookup tables. With fixed L, Δz, K, LebyD, and α, the change in pressure head Δh is evaluated for all ND×NL combinations of pipe diameter and link index:

While an algorithm evaluates a candidate solution, the pressure head at each node is sequentially calculated by “marching” through the network. Starting with the fixed source pressure head, the algorithm finds the pressure head hi for a given node by adding the head at the upstream node, hi−1 to the change in head for that link iL and the diameter iD under consideration. Thus,

Along with the hydraulic evaluation of a candidate solution, the cost of the partial candidate is found through the use of a lookup table C:

where C(iDiL) returns the additional cost of assigning a diameter with index iD to link iL. In this way, the candidate solution's hydraulic performance and cost are incorporated into the genetic algorithm and backtracking approaches. In contrast to GA, the backtracking algorithm evaluates pressure head and cost upon consideration of each partial candidate, where GA calculates these values on full candidates as part of the objective function.

4.1 BT and GA pre-processor 1: maximum available diameter

To increase the efficiency of BT and GA, it is advantageous to limit the number of pipe diameters in the available set, especially those outside of the range of the optimal solution. For the BT algorithm in particular, larger diameters can require considerable computational effort, since they tend not to violate static head requirements and require multiple-link partial candidates for the algorithm to reject them once their cost exceeds that of an already-found viable candidate. Therefore, a pre-processor is used to provide a maximum diameter (Dmax) that should be considered during the optimization process. This procedure, which produces a conservative estimate, finds the smallest diameter at which a network with a single pipe diameter choice produces no nodes with a pressure head below hmin, similar to the technique used by Mohan and Jinesh Babu (2009). After this diameter is found, the next larger diameter in the set is selected as Dmax to allow the algorithm to select a larger than necessary diameter if this is able to save cost elsewhere. It worth noting that Kadu et al. (2008) presents another method to further prune the search space with the critical path concept, where Dongre and Gupta (2011) noted the computational advantages of having just four diameter choices per link. This method, however, may prune the global optimum and may not produce feasible head values at intermediate nodes, as in the case of networks with a local high point.

4.2 BT and GA pre-processor 2: adjusted minimum pressure head

A second pre-processor adjusts the minimum pressure head requirement for each internal node by considering the total head required at downstream nodes. It can be recognized that, without the use of a pump, the total head cannot increase at nodes downstream of a given node i. Furthermore, the total head must decline at a minimum grade that is determined by the demand volume flow rate and the largest pipe diameter available (Dmax) for selection. This energy constraint is utilized to reduce the number of candidates to be considered by increasing the minimum pressure head at nodes where these rules produce a higher minimum head than the original hmin. For example, nodes upstream of a local network high point can have their minimum pressure head increased beyond the normal minimum, since the pressure head must be great enough to ensure adequate flow to the higher elevation downstream node. To begin this process, each node i is initialized with a baseline minimum total head:

is thus initialized by considering only the node's hydraulic requirements in isolation, i.e., without acknowledging the neighboring downstream nodes. The pre-processor then considers updating by checking the following condition, which is false when the minimum pressure head at downstream nodes produces further constraints on an upstream node i. Thus, for all nodes i which are upstream of some node j, the following inequality can be evaluated:

Also, consider that when flow rate Qi−j is small and Dmax is large, the right-hand side of Eq. (26) approaches zero, representing the simple statement that upstream total head must always be greater than downstream total head. When the condition in Eq. (26) is false, the minimum total head can be updated in node i such that the maximum diameter size in link i−j is able to meet the downstream node's minimum total head, or

In this way, may be updated for each node until the condition in Eq. (26) is true for all nodes i with a downstream node j connected by a single link.

After the values for are updated, they are converted back into minimum pressure head values by subtracting the elevation zi from . This pre-processor serves to narrow the search for viable candidate solutions by potentially increasing the minimum pressure head. Since backtracking and GA consider network links in the downstream direction, these algorithms are otherwise blind to future downstream pressure head requirements. This limitation is alleviated by the pre-processor, which allows these algorithms some implicit information about what local diameter choices will be viable for the full network solution. Note that both pre-processors discussed will not prune the global optimum from the solution.

4.3 Backtracking algorithm (BT)

The backtracking algorithm is a partial enumeration method that employs a systematic search of candidate solutions to find a global optimum. The algorithm works recursively to incrementally build candidate solutions while checking the candidates for hydraulic and cost acceptability. The strength of the BT is that, upon discovery of an infeasible partial candidate, all extensions of that candidate can be eliminated from consideration. In this way, many solutions can be pruned from the solution tree to achieve greater computational efficiency.

Two backtracking methods in the literature are those by Gessler (1985) and González-Cebollada et al. (2011). The algorithm proposed by Gessler proposes a pipe-grouping strategy which speeds up the algorithm but risks pruning the global optimum. Additionally, pipe grouping represents its own optimization problem (Raad, 2011). The González-Cebollada algorithm does not include such pipe-grouping criteria, although it does halt its search after finding the first feasible solution, thus it does not guarantee a global optimum. The present study's BT algorithm, once run to completion, does guarantee a global optimum. It operates similarly to the method presented by González-Cebollada et al. (2011), with the major differences being that the algorithm continues searching once it has found its first feasible solution and uses pre-processors 1 and 2 to further reduce the search space. This implementation of BT, however, scales poorly with larger network sizes and would not be appropriate for use on large urban networks. Its appropriateness is shown here for many of the GDWNs encountered in practice, as evidenced by its use on real-world GDWN test cases in this paper. Moreover, it serves as a benchmark against which other algorithms can be compared.

BT uses two rejection criteria to discard candidate solutions from further consideration. The first rejection criterion is that when a candidate violates pressure head constraints, all candidates with equal or lesser diameter sizes can be discarded. This condition is leveraged even more effectively with pre-processor 2 above, which can increase pressure heads at individual nodes by anticipating the head requirements at surrounding nodes. The second rejection criterion is that once a feasible candidate has been found, all other partial candidates with a higher cost can also be discarded. The BT algorithm further extends this second criterion by considering that the links yet to be considered in a partial candidate, an “extension” to the partial candidate, will cost at a minimum that of the entire extension being composed of the smallest available diameter.

The backtracking algorithm begins its search of the solution tree by considering the partial candidate with the smallest diameter size assigned to the first network link. The pressure head and the partial candidate cost at the outlet node are calculated with the Δh and C lookup tables. If this partial candidate meets pressure head and cost requirements, the algorithm extends this partial candidate by assigning the smallest diameter to the downstream link. If a partial candidate produces a node that is rejected on the basis of pressure head, the next largest larger diameter is chosen for the link upstream of the node. If no diameter satisfies the pressure head condition, the algorithm backtracks to the upstream link and assigns a larger diameter to the link. In this way, the algorithm continues to extend and reject candidate solutions until a full candidate satisfies the pressure head requirements. Once a working solution has been found, candidate solutions may be rejected based on cost. For each new candidate, cost is calculated by adding the cost of diameters that have already been assigned to the cost of assigning all downstream links with the smallest diameter available. If this cost exceeds the cost of the running optimum, the partial candidate is rejected. While the minimum pressure head criterion tends to prune candidates with diameters that are too small, the cost-based criterion tends to prune candidates of diameters that are too large.

4.4 Modified backtracking algorithm (BT-NoUp)

A modification to the BT algorithm was made to further improve its computational speed, although at the risk of pruning the global optimum from the search. This modified algorithm (BT-NoUp) rejects all candidates that feature a smaller diameter that is upstream of a larger diameter when an equal or smaller flow rate is present in the downstream link. Typically, a network designer would not consider such designs, and in cases where a single source feeds into a network with constant-length links, it is advantageous (or equivalent) to place larger diameters upstream of smaller diameters. However, due to the discrete nature of diameter choices and link lengths, an optimization problem may, in fact, have an optimal candidate with a larger diameter downstream from smaller ones. For this reason, the BT-NoUp algorithm, unlike the BT algorithm, may miss the global optimum at the expense of its greater computational efficiency.

4.5 Genetic algorithm (GA)

Genetic algorithms are stochastic optimization techniques that mimic the process of natural selection, and numerous variations of GAs have demonstrated acceptable performance on WDN design (Nicklow et al., 2010). Given their popularity, the GA included in this study is meant to provide a point of comparison to the BT and CB algorithms when applied to GDWNs.

When implemented in water network design, each candidate solution represents a selection of pipe diameters. The algorithm is initialized with a population of candidates of size Nc that repeatedly undergoes the processes of mutation, crossover, and selection

where each candidate in the population ci contains NL diameters. In the present work, candidates are represented as a string of natural numbers, which is used over a binary representation to improve the ease of encoding (Vairavamoorthy and Ali, 2000). The mutation operator replaces pipe diameters with a diameter from a uniform random distribution, where each link diameter has a probability of pmut of mutating on each generation. The crossover operator randomly pairs individuals in the population with probability pxover and performs a single-point crossover of the two individuals, where the point of crossover is randomly chosen. The fitness, fi, of each candidate is assessed with penalties associated with the solution's pipe cost, Cpipe,i, and hydraulic cost, Chyd,i, which is assigned when violations of the pressure head requirements occur:

The hydraulic cost is found for each individual by identifying nodes in which the pressure head is less than hmin and multiplying the total amount of head violation by a hydraulic penalty coefficient, ahyd:

To allow for a hydraulic penalty coefficient to produce similar results in both small-scale (inexpensive) network and a large-scale (more expensive) cases, the hydraulic penalty coefficient is made directly proportional to the average solution cost. With each generation, ahyd is updated by multiplying the normalized penalty coefficient, ahyd,norm, by the average pipe cost of the population,

The algorithm then selects candidates to be carried into the next generation with a tournament selection method, where Nc groups of s individuals are randomly assigned and the fittest candidate among each group is selected, thus replacing the previous population with an equally sized population of Nc individuals.

In this study, the genetic algorithm parameters used were Nc=200, pmut=0.05, pxover=1, Ngen=500, , and s=10. These parameters were chosen by systematically varying parameter values until the optimum cost of a network, case 2, could no longer be significantly improved. The first four of these values are in line with typically used values from Simpson et al. (1994) of Nc (30–200), pmut (0.01–0.05), pxover (0.7–1.0), and Ngen (100–1000).

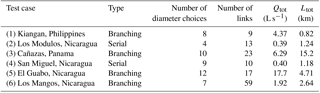

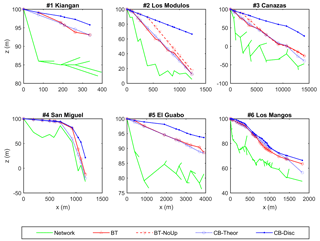

Six cases were studied based on actual GDWN in Panama, Nicaragua, and the Philippines. Global characteristics of each network are presented in Table 1 and the details of each network are presented in Table 4a–f. Each network is a branching type without loops. The total lengths of the networks range from less than 1 to over 15 km. Two serial networks are tested to demonstrate the effect of a local high point on the algorithm solutions. Elevation plots for each case are shown in Fig. 5.

The choice of hmin is not standardized, and should appropriately balance the risk of negative pressure in pipes and the increase in network cost due to the requirement of using larger diameters. The choice of hmin in GDWN design is typically in the range of 5–20 m (Arnalich, 2010; Bouman, 2014; Swamee and Sharma, 2008). In the present study hmin = 7 m, although this requirement was reduced at selected nodes at the beginning of a network where changes in elevation are still small (case 2, where the pressure head at node 2 is relaxed to 2 m). At the source node, the pressure head is fixed at atmospheric pressure. All cases assumed minor-lossless flow, although all algorithms (e.g., Eq. 18 for CB-Theor) are capable of handling minor loss coefficients through the equivalent length method as described above. All algorithms were run in a late-version of MATLAB (or Mathcad for CB) on an Intel i5 processor at 2.50 GHz.

The mapping between continuous diameters and the discrete nominal pipe sizes was accomplished in our solution in one of the following ways:

-

For small and moderate size networks, the designer may manually adjust the pipe sizes (downward, normally one pipe size) starting from the first link downstream from the source and continuing along the rest of the distribution main to the end in a step-by-step manner. A nearby plot of the pressure heads compared with the theoretical Dij from the CB approach (e.g., on the same Mathcad page for our solution) will highlight the acceptability or unacceptability of any change. This exercise also gives the designer valuable understanding of the sensitivity of the design to small changes in pipe sizes.

-

Based on the theoretical Dij from the CB approach, a split-pipe can be created for each link. That is, the lengths for the two discrete pipes sizes that bound the theoretical Dij from above and below are calculated such that the pressure drop between two consecutive nodes in the distribution main matches between the composite pipeline and the CB approach. This also provides discrete pipe sizes that nearly match the CB solution in terms of cost.

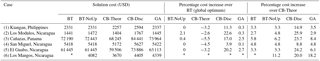

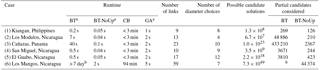

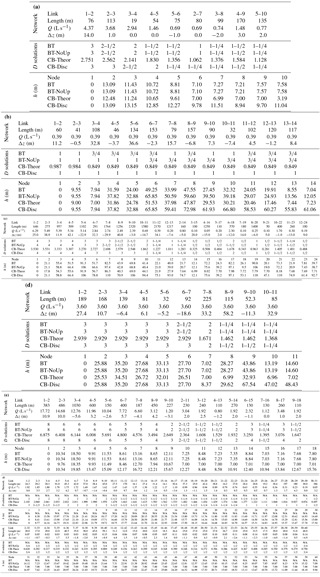

The current study evaluated three types of algorithms that optimize the design of gravity-driven water networks (GDWN). The algorithms include the calculus-based (CB) algorithm (Eq. 18), a backtracking algorithm (BT) and its modified version (BT-NoUp), and a genetic algorithm (GA). The algorithms were applied to six test cases that are based on real GDWNs. Our results show that the CB, GA, and BT-NoUp algorithms could find solutions to the GDWNs within 25 % of the BT global optimum. All cases assume minor-lossless flow and a two-part pipe-cost model. Solution costs from each algorithm are shown in Table 2 and runtime statistics are shown in Table 3. BT could run to completion in < 1 min in all but the largest case (case 6 with 59 links), which did not complete after 7 days. As such, cost comparisons to BT are not made for case 6.

Table 3Runtime and size of solution space for each algorithm.

a BT, BT-NoUp, and GA algorithm run times do not include approximately 2 s of pre-processing time. b BT did not complete case 6 after 7 days of runtime.

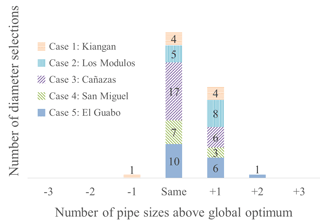

Figure 6Diameter sizes from calculus-based (CB-Disc) solutions compared with global optimum solutions (from backtracking, BT). A global optimum for case 6, Los Mangos, is not included since BT did not complete after 7 days of runtime.

The CB algorithm based on Eq. (18), unlike the other algorithms in this work, finds a solution with theoretical diameters that are drawn from a continuous domain (CB-Theor). For all test cases, the costs of the CB-Theor solutions was less when compared with the BT discrete-diameter global optimum (5.5 to 2.6 % lower cost than BT). In fact, because of the discrete pipe sizes needed for an actual network, the continuous model will always produce the smallest theoretical network cost. The CB algorithm then maps this solution to a commercially-available discrete set (CB-Disc). The mapping process used in this study simply mapped each theoretical diameter to the nearest available diameter of a larger size, thus producing a solution which still satisfies static head requirements but with a higher associated material cost. This tended to oversize the diameters, although the CB-Disc solutions were always within two diameters of the known global optimum solutions, as shown in Fig. 6. From all the combined test cases with known global optima, all but one (71 out of 72) of the diameter selections were within one diameter of the global optimum. More sophisticated mapping schemes, like independently adjusting D for each link in the distribution main in a step-by-step manner starting with the source while ensuring all pressure head constraints are satisfied, would be more likely to produce results identical to the global optimum (see Sect. 6). This was performed in the current study but the results are not presented because of space constraints. The CB-Disc solution costs were, in all cases, larger than the global optimum, with costs ranging from 3.9 to 22.6 % above the global optimum. Thus, for all cases, the calculus-based algorithm bounded the cost of the global optima with a lower-cost CB-Theor solution and a higher-cost CB-Disc solution. This trend is a result of the additional constraints imposed by the finite set of diameter choices. If the algorithm is allowed a greater number of discrete diameter choices, i.e., through adding a less-common nominal diameter size to the available set, the cost of the CB-Disc solution would approach the CB-Theor solution. For all but case 6, the CB algorithm converged on a solution in 3 min or less.

Table 4Case network properties, diameter (D) results (inch nominal sizes, with CB-Theor in inches), and nodal h (in meters) for (a) Case 1, Kiangan, (b) Case 2, Los Modulos, (c) Case 3, Cañazas, (d) Case 4, San Miguel, (e) Case 5, El Guabo, and (f) Los Mangos.

BT-NoUp, a modified version of BT which does not consider smaller diameters upstream of large diameters, completed itself within 4 s for all cases, and found solutions which matched or came very close to the BT global optimum. BT-NoUp missed the global optimum in cases 2 and 3, although by a small percentage increase in cost (2.1 and 0.4 % respectively). BT-NoUp, however, finished its search in a shorter amount of time in comparison to BT, a benefit that becomes relevant on problems with larger solution spaces, such as cases 3 (1.0 × 1023 candidate solutions) and case 6 (7.3 × 1049 candidate solutions).

GA was run on each case a total of 100 times, each run itself evolved 200 candidates for 500 generations. The lowest-cost candidate amongst the final population that did not violate the pressure head condition was chosen as the GA solution. Because GA is a stochastic search algorithm producing different results from run-to-run, the costs of the optima from all 100 runs were averaged, with this averaged value presented in Table 2. Overall, GA costs came close to the global optima (within 3 %) for cases 1–5 where the global optimum was known from BT. GA solution costs increased with larger network sizes, with its solution cost 18 % higher than CB-Theor for case 6, the largest case run. Each GA run finished consistently within 1–5 s, not including about 2 seconds of pre-processor time. We note that variations of GAs have been reported in the literature and several of these may improve upon the GA results obtained in this study. Potential improvements to the GA a self-adapting penalty function (Wu and Walski, 2005), the use of elitism to preserve the best solutions (Kadu et al., 2008), and a reduction in the search space (Kadu et al., 2008). One reported improvement, the scaling of the fitness function to magnify the rewards towards slightly fitter candidates at later generations (Dandy et al., 1996), was attempted for case 2 but did not result in a noticeable effect on performance.

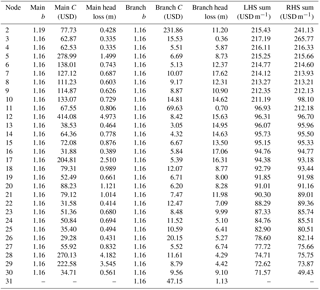

Table 5Optimization results from Bhave (1978) algorithm. LHS sum and RHS sum are the left and right sides of his Eq. (19), which should be equal.

To visually compare the algorithm solutions, the hydraulic grade lines from BT, BT-NoUp, CB-Theor, and CB-Disc are presented in Fig. 5 along with the network elevation for each test case. For clarity, the hydraulic grade lines of branch links are omitted from the figure. In addition, the GA solutions are omitted since 100 solutions were obtained for each test case. Collectively, the hydraulic grade lines reveal a close alignment of the BT solution (the global optimum) with the CB-Theor solution which utilizes a continuous diameter set. Furthermore, the mapping scheme used to generate a CB-Disc solution is shown to increase pipe sizes in some cases far beyond the limit imposed by hmin, which was set to 7 m in the present work.

We compared the CB results for the Los Mangos network with those from the Bhave (1978) optimization algorithm (see Table 5). Like Eq. (15) in the present work, Bhave's optimality equation (his Eq. 19) equates the sum of a weighted term for all links entering and leaving each internal node in the distribution main. In the present work the term is proportional to the hydraulic gradient and the weighting factor is proportional to flow rate. In Bhave's case the term is the ratio of pipe cost to head loss, where the weighting factor is pipe-cost exponent b. There are 60 nodes for this network, including 30 nodes in the distribution main. The rest are delivery nodes (note there are 2 branches from node 30 of the distribution main). The terms required for the calculations include b, pipe cost, and head loss in the main and branches. The designation LHS refers to nodes in the distribution main entering, and RHS to those leaving, the node at the far-left side of Table 5. The exponent b comes from curve fitting pipe-cost data to the two-part pipe-cost model. Linear interpolation was used between diameters Dco and Dco+1 to obtain b in this range. Except for a few nodes, agreement between the two CB algorithms is very good. Although Bhave's Eq. (19) and Eq. (18) in the present work, appear quite different due to the different ways each was developed, both produce optimality for the networks considered in this paper. The key distinction between the two developments is the assumption of constancy in terms that comprise the coefficient A in Bhave (his Eq. 13), mainly the exponent b (m in his paper). In general, b depends on pipe diameter, thus making b=b(D) for multi-part cost models. When taking derivatives to obtain the final algorithms in both works, this dependence must be included, which produces additional terms in the optimization equation (see our Eq. 18 above). However, if the system of equations is solved by an iterative method, as Bhave proposed, the dependency may be neglected (though issues with convergence of the numerical solution may arise because of this). It is very important to note that if a non-iterative method is used to solve the system of equations as done in the present work (using a commercial program like Mathcad), all terms in the governing equations must be treated as continuous, not discrete, and the b=b(D) dependence must be explicitly included. It should also be noted that the optimization algorithm of Eq. (18) in this paper includes minor loss, which is not included in the Bhave (1978) work.

Algorithms to optimize the cost of branching gravity-driven water networks are evaluated on six test cases from real networks in the Philippines, Nicaragua, and Panama. A calculus-based algorithm produced a solution composed of theoretical diameters from a continuous set (CB-Theor), which are then mapped onto discrete commercially available diameters (CB-Disc). Backtracking (BT), a recursive algorithm, systematically searches discrete candidate solutions and, when run to completion, is guaranteed to find the global optimum by following rules that prune only higher-cost or hydraulically infeasible candidates. The BT algorithm was modified (BT-NoUp) to improve computational speed by rejecting all candidates that included a small diameter directly upstream of a larger diameter but allowed for the possibility of missing the global optimum. The third type of algorithm evaluated was a genetic algorithm (GA) that used single-point crossover and tournament selection.

BT could find the global optimum in most test cases with relatively little computational effort, although its poor scaling to larger networks is evidenced by its inability to find a solution to case 6, a network with 60 nodes and 59 links. The BT-NoUp completed its search in less time than BT and could find a solution to case 6. Based on case 1–5 results, the extra pruning condition adopted in BT-NoUp sacrificed only small cost increases. Both BT and BT-NoUp, however, could become prohibitively time-consuming when dealing with networks with significantly more links, diameter choices, or an unfavorable layout. While the test cases represent the range of GDWN sizes encountered in the authors' experience, future work would be needed to verify the suitability of the BT and BT-NoUp algorithms on larger GDWNs. The calculus-based algorithm produced consistently good results for the networks tested, although a more robust mapping scheme from theoretical diameters to discrete diameters would further improve on these results as discussed above. In potential future work, the CB-Theor solutions could be used to prune the BT search space, like Kadu et al. (2008), by only including the two diameters above and below the CB-Theor diameters, producing four diameter choices per link. The calculus-based methodology provides an additional benefit to the designer by explicitly revealing the sensitivities to cost for a design. The calculus-based algorithm requires greater computational effort than backtracking for smaller networks, however, this effort scales more linearly with the number of network links, while backtracking scales exponentially. Furthermore, backtracking's computational time is sensitive to the number of available diameters. Still, when applied to the present study's GDWN test cases with a modest number of links (23), backtracking quickly found a global optimum. In addition, because it is guaranteed to find the global optimum, it can be useful for benchmarking the performance of other algorithms which scale better with more network links. While the genetic algorithm produced solutions with good proximity to the global optimum, its solution costs tended to be further from the global optimum in cases with more links.

For all test cases, the calculus-based algorithm's theoretical diameter solutions (CB-Theor) produced a lower cost than the discrete-domain global optimum. This result is made possible because it is not constrained to a discrete set of diameters. As such, the CB-Theor results represent a lower-bound on the optimum solution within the problem formulation, which could be approached with a finer selection of pipe diameters. We also demonstrated good agreement between the CB-based optimization algorithm developed here and that of Bhave (1978). Though Bhave's algorithm and Eq. (18) in the present work appear quite different due to the different ways each was developed, both produce optimality for the networks considered in this paper. The key distinction between the two developments is that Bhave assumed exponent b constant in the pipe-cost model, which was justified based on his iterative method of solution. In the present work, which uses a commercial program to solve the nonlinear governing equations for D and h, b(D) dependence is explicitly included for multi-part cost models. Contrasted with Bhave, minor losses are included in the CB optimization algorithm in the present work.

All survey data from the network cases tested are available in Table 4.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work was partially supported by the Villanova Undergraduate Research Fellowship Program and the Goldwater Foundation.

Edited by: Luuk Rietveld

Reviewed by: three anonymous referees

Alperovits, E., and Shamir, U.: Design of optimal water distribution systems, Water Resour. Res., 13, 885–900, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR013i006p00885, 1977.

Arnalich, S.: How to design a Gravity Flow Water System, Arnalich – Water and Habitat, 2010.

Bhave, P. R.: Optimization of Gravity-Fed Water Distribution Networks: Theory, J. Environ. Eng.-ASCE, 109, 189–205, 1983.

Bhave, P. R.: Non-computer optimization of single source networks, J. Environ. Eng.-ASCE, 104, 799–814, 1978.

Bhave, P. R.: Optimal design of water distribution networks, Alpha Science International Ltd., Pangbourne, UK, 2003.

Bouman, D.: Hydraulic design for gravity based water schemes, Aqua for All, Den Haag, the Netherlands, 2014.

Churchill, S. W.: Friction factor equation spans all regimes, Chem. Eng. J., 84, 91–92, 1977.

Colebrook, C. F. and White, C. M.: Experiments with fluid friction in roughened pipes, P. R. Soc. London, 161, 367–381, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1937.0150, 1937.

Dandy, G. C., Simpson, A. R., and Murphy, L. J.: An improved genetic algorithm for pipe network optimization, Water Resour. Res., 32, 449–458, https://doi.org/10.1029/95WR02917, 1996.

Dongre, S. R. and Gupta, R.: Discussion of `Recursive Design of Pressurized Branched Irrigation Networks' by César González-Cebollada, Bibiana Macarulla, and David Sallán, J. Irrig. Drain Eng., 138, 697–697, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IR.1943-4774.0000441, 2011.

Gessler, J.: Pipe Network Optimization by Enumeration, Proceedings of the Specialty Conference on Computer Applications in Water Resources, American Society of Civil Engineers, New York, USA, 572–851, 1985.

González-Cebollada, C., Macarulla, B., and Sallán, D.: Recursive Design of Pressurized Branched Irrigation Networks, J. Irrig. Drain Eng., 137, 375–382, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IR.1943-4774.0000308, 2011.

Jones, G. F.: Gravity-driven Water Flow in Networks: Theory and Design, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011.

Kadu, M. S., Gupta, R., and Bhave, P. R.: Optimal design of water networks using a modified genetic algorithm with reduction in search space, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 134, 147–160, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2008)134:2(147), 2008.

Kansal, A., Gupta, R., and Bhave, P. R.: Optimization algorithms for design of branching water distribution networks, J. Indian Water Works Association, 28, 135–140, 1996.

Keedwell, E. and Khu, S.: Novel Cellular Automata Approach to Optimal Water Distribution Network Design, J. Comput. Civil. Eng., 20, 49–56, 10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3801(2006)20:1(49), 2006.

Kessler, A. and Shamir, U.: Analysis of the Linear Programming Gradient Method for Optimal Design of Water Supply Networks, Water Resour. Res., 25, 1469–1480, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR025i007p01469, 1989.

Krapivka, A. and Ostfeld, A.: Coupled genetic algorithm – Linear programming scheme for least cost design of water distribution systems, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 135, 298–302, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2009)135:4(298), 2009.

Maier, H. R., Simpson, A. R., Zecchin, A. C., Foong, W. K., Phang, K. Y., Seah, H. Y., and Tan, C. L.: Ant colony optimization for design of water distribution systems, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 129, 200–209, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2003)129:3(200), 2003.

Martin, Q. W.: Optimal design of water conveyance systems, J. Hydr. Eng. Div.-ASCE, 106, 1415–1433, 1980.

Mohan, S. and Jinesh Babu, K. S.: Water distribution network design using heuristics-based algorithm, J. Comput. Civil. Eng., 23, 249–257, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3801(2009)23:5(249), 2009.

Monbaliu, J., Jo, J., Fraisse, C. W., and Vadas, R. G.: Computer aided design of pipe networks, Proc. Int. Symp. On Water Resource Systems Application, Friesen Printers, Winnipeg, Canada, 1990.

Nicklow, J., Reed, P., Savic, D., Dessalegne, T., Harrell, L., Chan-Hilton, A., Karamouz, M., Minsker, B., Ostfeld, A., Singh, A., Zechman, E., and ASCE Task Committee on Evolutionary Computation in Environmental and Water Resources Engineering: State of the Art for Genetic Algorithms and Beyond in Water Resources Planning and Management, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 136, 412–432, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000053, 2010.

Prasad, T. D. and Park, N. S.: Multiobjective genetic algorithms for design of water distribution networks, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 130, 73–82, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2004)130:1(73), 2004.

Raad, D. N.: Multi-objective optimisation of water distribution systems design using metaheuristics, PhD thesis, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2011.

Saldarriaga, J., Páez, D., Cuero, P., and León, N.: Optimal Design of Water Distribution Networks Using Mock Open Tree Topology, World Environmental and Water Resources Congress, 19–23 May 2013, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, 869–880, 2013.

Samani, H. M. V. and Mottaghi, A.: Optimization of water distribution networks using integer linear programming, J. Hydraul. Eng., 132, 501–509, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2006)132:5(501), 2006.

Simpson, A. R., Dandy, G. C., and Murphy, L. J.: Genetic Algorithms Compared to Other Techniques for Pipe Optimization, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 120, 423–443, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(1994)120:4(423), 1994.

Streeter, V. L., Wylie, E. B., and Bedford, K. W.: Fluid Mechanics, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, USA, 1998.

Suribabu, C. R.: Heuristic-based pipe dimensioning model for water distribution networks, J. Pipeline Syst. Eng., 3, 115–124, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)PS.1949-1204.0000104, 2012.

Swamee, P. K. and Jain, A. K.: Explicit equations for pipe flow problems, J. Hydr. Eng. Div.-ASCE, 102, 657–664, 1976.

Swamee, P. K. and Sharma, A. K.: Gravity low water distribution network design, J. Water Supply Res. T., 49, 169–179, 2000.

Swamee, P. K. and Sharma, A. K.: Design of Water Supply Pipe Networks, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008.

Taorimina, R. and Chau, K. W.: Data-driven input variable selection for rainfall–runoff modeling using binary-coded particle swarm optimization and Extreme Learning Machines, J. Hydrol., 529, 1617–1632, 2015.

Tospornsampan, J., Kita, I., Ishii, M., and Kitamura, Y.: Split-pipe design of water distribution network using simulated annealing, International Journal of Computer, Information, and Systems Science, and Engineering, 1.3, 153–163, 2007.

Vairavamoorthy, K. and Ali, M.: Optimal design of water distribution systems using genetic algorithms, Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng., 15, 374–382, https://doi.org/10.1111/0885-9507.00201, 2000.

Vasan, A. and Simonovic, S. P.: Optimization of water distribution network design using differential evolution, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 136, 279–287, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2010)136:2(279), 2010.

Wu, Z. Y. and Walski, T.: Self-adaptive penalty approach compared with other constraint-handling techniques for pipeline optimization, J. Water Res. Plan. Man., 131, 181–192, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2005)131:3(181), 2005.

Yang, K. P., Liang, T., and Wu, I. P.: Design of conduit system with diverging branches. J. Hydr. Eng. Div.-ASCE, 101, 167–188, 1975.

Zhao, W., Beach, T., and Rezgui, Y.: Optimization of Potable Water Distribution and Wastewater Collection Networks: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions, IEEE T. Syst. Man Cyb., 46, 659–681, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2015.2461188, 2016.

Zheng, F., Simpson, A. R., and Zecchin, A. C.: A decomposition and multistage optimization approach applied to the optimization of water distribution systems with multiple supply sources, Water Resour. Res., 49, 380–399, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012WR013160, 2013.