the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Consumption of safe drinking water in Pakistan: its dimensions and determinants

Safe drinking water is one of the basic human needs. Poor quality of drinking water is directly associated with various waterborne diseases. The present study has attempted to analyze the household preferences for drinking water sources and the adoption of household water treatment (HWT) in Pakistan by using the household data of Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018 (PDHS, 2018). This study found that people living in rural areas, those with older heads of household and those with large family sizes are significantly less likely to use water from bottled or filtered water. Households with media exposure, education, women's empowerment in household purchases and high incomes are more likely to use bottled or filtered water. Similarly, households are more likely to adopt HWT in urban areas, when there is a higher level of awareness (through education and media), higher incomes, women enjoy a higher level of empowerment, and piped water is already used. However, households that use water from wells and have higher family sizes are less likely to adopt water purifying methods at home.

Access to clean and safe drinking water is a basic human right. However utilization of contaminated water is increasing (particularly in developing countries). Approximately 12 % of the world population lacks access to safe drinking water (World Economic Forum, 2019). It has been estimated that approximately 785 million people worldwide are drinking water from unimproved sources; 207 million people have to spend at least 30 min to reach water source, and 144 million people get drinking water from rivers, streams or lakes (WHO/UNICEF, 2019).

Consequently, unsafe water leads to chronic diseases like typhoid, diarrhea, cholera and parasites (Curry, 2010). It has been estimated that due to diarrhea, around 1.3 million people die annually; among them 88 % are children (IHME, 2015). Consumption of safe drinking water can prevent the fatal cases of diarrhea (Fewtrell et al., 2005). This is supported by the fact that during 1870–1930 due to the provision of piped water in the urban areas of the USA, mortality rates had declined rapidly (Cutler and Miller, 2005). However, Brick et al. (2004) and Checkley et al. (2004) were of the view that to achieve the maximum health benefits by using clean water, there is a need for sanitation and hygiene conditions to also be improved.

Pakistan ranks ninth on the list of top 10 countries without access to safe drinking water. In Pakistan, having a population of 207 million in 2018, 21 million people did not have access to safe drinking water (Water Aid, 2018). Similarly, the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR, 2012) concluded that the quality of water has deteriorated over the years because of the contamination of chemical pollutants and human waste.

Provision of clean water to the households can be achieved in two ways: by supplying treated water at the point of collection and household water treatment (HWT). In the first approach, studies found that significant re-contamination can occur during the process of transportation and storage of the water, and even storage material and duration affects the water quality (Checkley et al., 2004; Brick et al., 2004). Brick et al. (2004) and Fewtrell et al. (2005) argued that HWT is the more effective method for the provision of safe drinking water as compared to supplying treated water at the point of collection. Examples of HWT are boiling (Mintz et al., 1995), chemical treatment (Quick et al.,1999) and chlorination (Clasen et al., 2015). However, various studies concluded that despite having positive impacts adoptability of HWT is very limited (Brown and Clasen, 2012).

Consumer behavior regarding the adoption of HWT is affected by numerous factors. Past studies have found that income (Bruce and Gnedenko, 1998), education (Dasgupta, 2001; McConnell and Rosado, 2000), education of female household members (Jyotsna et al., 2003), age of household head (Mintz et al., 2001), household size (Sattar and Ahmad, 2007), level of awareness (Quick et al., 1999; Jalan et al., 2009), cost of HWT methods (Jalan and Somanathan, 2008), wealth of the household (Fotue et al., 2012), locality of residence (Bruce and Gnedenko, 1998), type of water source (Daniel et al., 2019), and perception about water quality and usefulness of HWT (Daniel et al., 2018) are the key factors in determining the adoption of HWT.

Very limited studies are being conducted on determinants of a household's preference for drinking water sources. In this regard, Abrahams et al. (2000) found that perceived risk of using tap water, age, income and race are important factors in the usage of bottled water. Haq et al. (2007) found that education of household head and quality of available water play a significant role in determining the demand of improved water sources in Pakistan. Rauf et al. (2015) found that family size and distance of the house from the water source have a negative impact on the consumption of safe drinking water sources. Zulfiqar et al. (2016) concluded that living in urban areas has a positive effect, while age of household head and the incidence of water-borne disease to any household member have a negative impact on the use of drinking water from improved sources.

The present study is an attempt to analyze the household preferences and the impacts of different socioeconomic factors on drinking water sources and adoption of HWT in Pakistan.

The data of Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017–2018 were used. In PDHS 2017–2018, 15 068 households were selected. The data on the source of household drinking water as well as the treatment measures adopted by households to clean the water were used.

To examine the role of different socioeconomic factors in determining the water source, the multinomial logit (MNL) model was used. That was because the dependent variable is multi-categories. By using MNL, we examined the preference for different drinking water sources by using bottled/filtered water as the base category. Similarly, logit model was applied to analyze whether a household applies any measure to clean the water at home or not. In this regard, a binary variable was created that takes the value of 1 if the household adopts any water treatment method and 0 for not adopting any HWT. Both models were estimated by using STATA 13.0. A brief description of the variables that are used in the analysis is summarized below.

2.1 Dependent variables

2.1.1 Source of drinking water

In the survey, there are 17 different water sources. However, depending upon the nature of these sources we had grouped them into six different water sources. These are (1) bottled/filtered water, (2) piped water, (3) protected well, (4) unprotected well, (5) surface water and (6) bought water from commercial entities.

2.1.2 Adoption of any purifying method to clean the water

We had created a binary variable to represent purifying methods used by the households. It takes the value of 1 if the household adopts any type of purifying method at home and 0 if the household does not adopt any purifying method.

2.2 Independent variables

2.2.1 Age of household head

It is hypothesized that households with older heads are less likely to use safe drinking water and adopt modern purifying methods. The following age categories were used: 15–25, 25–39, 40–59 and 60 or more years of age.

2.2.2 Level of education of household head

In the dataset, education is divided into four categories: none, primary, secondary and higher education. We hypothesize that education will positively affect the choice of safe drinking water sources and the use of purifying methods.

2.2.3 Household size

It is hypothesized that household size will reduce the chances of using bottled/filtered water as well as of adopting HWT. This variable is categorized as the family size of 1–5, 6–10, 11–15 and 16 or more members.

2.2.4 Wealth of household

The wealth index was used to describe the wealth of the household. The wealth index is calculated in PDHS by using the principal component analysis of around 40 different asset variables including the housing facilities, assets and other material. The wealth index can take values from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates the poorest and 5 the richest household. It is hypothesized that wealth will increase the chances of using bottled/filtered water and of adopting HWT.

2.2.5 Exposure to media

We constructed a binary variable named exposure of media (reading the newspaper, watching TV or listening to the radio). It takes the value of 1 if a household either reads the newspaper, watches TV or listens to the radio, indicating that the household has exposure to media. This study hypothesizes that media exposure will increase the likelihood of using bottled/filtered water and of adopting HWT.

2.2.6 Women's empowerment

There are several aspects of women's empowerment. These include control over resources, involvement in household decision-making, and economic contribution in the household, freedom of movement, sense of self-worth, appreciation in the household, time use, knowledge, division in household work etc. (Akram, 2018). Keeping in mind the nature of the present study, we used only female autonomy in household purchases as an indicator of empowerment. In the dataset, the question has five responses: (1) respondent alone, (2) respondent and husband/partner, (3) husband/partner alone, (4) family elders and (5) others. To make binary variables in the study, the first two responses are assigned the value of 1, describing that a woman has autonomy, and 0 for the rest of the three options, indicating that she had no autonomy. It is hypothesized that women's empowerment will increase the likelihood of using bottled/filtered water and of adopting HWT.

2.2.7 Distance to the water source

To measure the relative distance to the water source, we utilized the information of walking distance (round trip) to get to the water source. The variable has three options: (1) water is available at home, (2) it takes up to 15 min to reach water source, and (3) it takes more than 15 min to reach a water source. We hypothesize that more distance to water will reduce the chances of using bottled/filtered water and of adopting HWT.

2.2.8 Location

Rural and urban areas are two bifurcations of the location. In this regard, a binary variable has been constructed assigning a value of 1 for rural households and 0 for urban households. It is hypothesized that households in urban areas are more likely to use bottled/filtered water and to adopt HWT.

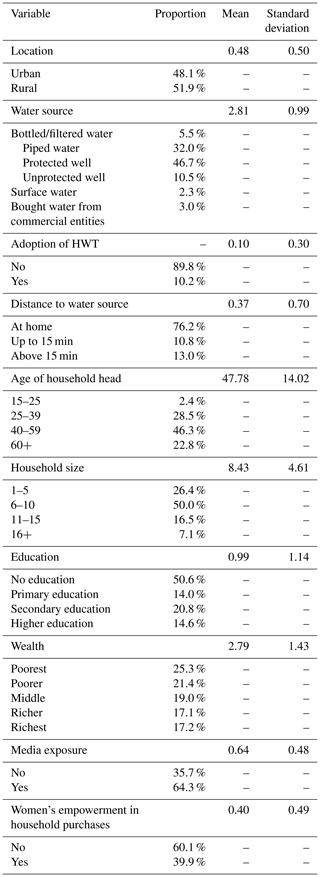

Descriptive statistics of variables are presented in Table 1. It shows that 48 % of the surveyed households were living in urban areas, while around 52 % of the sampled households were living in rural areas.

The majority of the households were drinking water from protected wells (47 %), followed by piped water (32 %), unprotected wells (11 %), bottled/filtered water (6 %) and other sources (4 %). Similarly, 90 % of households are not adopting any household water purifying method. The majority of households (i.e., 76 %) have drinking water at home, 11 % of households have to travel for less than 15 min to reach a water source and 13 % of households are getting water from sources where they have to travel for 15 min or more (round trip). The minimum age of the household head emerged as 15 years, while the maximum age was 95 years, with the average age of the household head being 48 years. It is also pertinent to mention that the majority of household heads belong to the age bracket of 40–59 years. The average family size is eight persons; however, the maximum family size of the surveyed households was 44 persons, and the minimum family size is only 1 family member. A total of 50 % of the households have a family size of 6–10 persons. Table 1 also indicates that 51 % of surveyed households were uneducated, and only 35 % of the households have a secondary level or higher education. In terms of wealth, 47 % of the households were poor, 19 % are among middle and 34 % were classified as rich. Table 1 also reveals that 64 % of the surveyed households have exposure to the media. Similarly, about 40 % of the households' women have empowerment in household purchases.

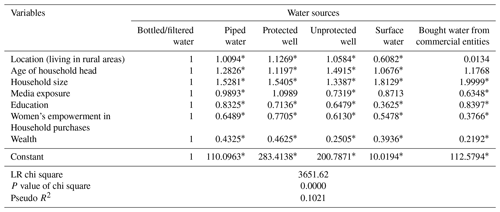

The study is focused on the determinants of household drinking water sources. For estimation, the MNL model has been applied. In the MNL model, we had used bottled/filtered water as the base category. The results are summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2Estimation results of multinomial logit (MNL) model of determinants of drinking water source.

∗ p<0.05.

The results suggest that a household's location influenced the choice of drinking water in four out of five alternatives. Zulfiqar et al. (2016) also came to the similar conclusion that living in an urban or rural area plays a significant role in determining a household's water source. The results suggest that people living in rural areas were more likely to use water from protected wells and tube wells compared to the water from other sources (a possible reason seems to be the cost and availability of services). Furthermore, results suggested that households in rural areas are less likely to use drinking surface water (relative risk ratio less than 1), but they would prefer piped water and also unprotected wells (relative risk ratio greater than 1).

Similar to the findings of Abrahams et al. (2000) and Zulfiqar et al. (2016) it has been found that the age of household head has a significant impact on the source of drinking water in all five alternatives. The results suggested that households with older heads are more likely to consume water from unprotected wells. This reflects that aged people in Pakistan are the least health-conscious, and they prefer to use traditional water sources.

Household size has a very strong impact, as the results are significant in all five alternatives. The results are also supported by the findings of Rauf et al. (2015). Households with a larger family size prefer to use other water sources. In comparison to the bottled/filtered water, as in all the alternatives the relative risk ratio is significantly greater than 1. With an increase in family size, water consumption increased, so families prefer to use water from those sources where they can get more water easily.

It has been confirmed that households having access to media and education are more likely to use water from protected wells or bottled/filtered water. This may be because people have information about the health hazards of unsafe water. Therefore they would prefer to use safe drinking water sources. Abrahams et al. (2000), Haq et al. (2007) and Zulfiqar et al. (2016) also came to a similar conclusion that education and awareness about the hazards of drinking unsafe water plays a crucial role in determining the improved drinking water source.

In line with the findings of Abrahams et al. (2000) it has been found that wealthier households prefer to use bottled/filtered water in comparison to other water sources. The reason may be that wealthier households can afford better sources of drinking water. Furthermore, rich people are more health-conscious and willing to spend more money on an improved water source.

It has also been found that households with greater women autonomy in making household purchases prefer to use bottled/filtered water in comparison to other water sources. This suggests that women are more health-conscious, and if they are involved in household spending decision-making, then there is a higher chance that they would make appropriate adjustments in the expenditures to allocate more money for using an improved water source.

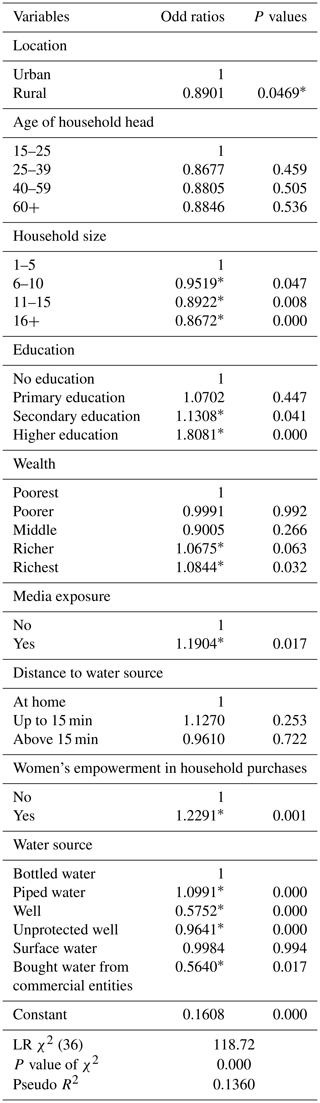

In the next step, the household's adoption of HWT was analyzed. This model is tested by using the logit model. The results are summarized in Table 3.

The results from Table 3 indicate that locality of the household plays a significant role in adoption of in-house water purifying treatment, and people who live in urban areas are more likely to adopt HWT (odd ratio for rural households is significantly below 1). These findings have also been supported by Bruce and Gnedenko (1998), who found that urban households are more likely to adopt HWT.

Similar to the findings of Sattar and Ahmad (2007), it has also been found that family size hurts the adoption of water purifying methods as odd ratios are less than 1. Due to the large family size, more water is required so it is very difficult for large families to adopt HWT. Rather, they prefer to use water without any treatment. This reveals the fact that, due to larger family size, quality and quantity of essential services are negatively affected.

Both education and exposure to the media (the indicators of the level of awareness) tend to increase the likelihood of adopting HWT. However, only secondary education and higher education result in increasing the chances of adopting HWT. These findings are supported by various past studies, including Dasgupta (2001), McConnell and Rosado (2000), Quick et al. (1999) and Jalan et al. (2009).

In line with the findings of Bruce and Gnedenko (1998) and Totouomet et al. (2012), it has been found that wealth of households has a significant impact on the adoption of water purifying methods. There are significantly higher odds of a wealthier household to adopt HWT in comparison to a poor or middle-income household.

Women's empowerment also had a significant impact on adoption of HWT. Households wherein women are empowered in making household purchases are more likely to use water-purifying methods. These results are supported by Jyotsna et al. (2003).

The drinking water source is also emerged as an important and significant factor in the adoption of HWT. The results indicate that people might not trust the water quality coming from the piped water (this has been supported by Daniel et al., 2018). Therefore, they are more likely to adopt HWT. Daniel et al. (2019) also came to the similar conclusion that households using piped water are more likely to adopt HWT. However, households using water from protected well, unprotected wells and water bought from commercial sources are significantly less likely to adopt HWT.

The present study is unable to find significant impact of age of household head and distance to water sources on the adoption of HWT in Pakistan. However past studies have found that the age of the household head (Mintz et al., 2001) plays a significant role in the adoption of HWT.

In developing countries, poor quality of drinking water has been recognized as a major health issue because many fatal diseases, especially diarrhea and hepatitis, are linked to the quality of water. The present study was conducted to analyze the role of different socioeconomic characteristics of households in using different water sources and adoption of HWT. The results of the study provide insight for policymakers to tackle obstacles in the consumption of safe drinking water in Pakistan, and it will help them to develop and adopt better policies that would increase the availability/usage of better quality drinking water in Pakistan.

It has been found that locality of household, family size, age of household head, wealth of household, level of awareness (education and exposure to media), and women's empowerment are significant factors in determining the household consumption of drinking water sources. People living in rural areas, headed by aged family members, and having large family sizes are significantly less likely to use improved drinking water sources. However, households with media exposure, education, women's empowerment in household purchases and belonging to the rich segment of society are more likely to use a safe drinking water source.

Similarly, locality of household, family size, education, exposure to the media, women's empowerment, source of drinking water and wealth of household are significant factors in determining the adoption of HWT. This reveals that households in urban areas, those with a higher level of awareness (through education and media), belonging to wealthy families, wherein women enjoy a higher level of empowerment and households using piped water are more likely to adopt HWT. However, households using water from protected well, unprotected wells, water bought from commercial sources and having higher family size are less likely to adopt water purifying methods at home. However, the age of household head and distance to water sources do not have a significant impact on the adoption of the water purifying method.

On the basis of the findings of the present study, the following is recommended:

- i.

Better drinking water facilities must be provided in rural areas so that differences in urban and rural areas in terms of safe drinking water may be eliminated.

- ii.

The study reveals that most Pakistani households get drinking water from wells. However excessive use of wells and tube wells has resulted in significant reduction in groundwater levels. There is a need for the government to launch awareness campaigns in order to promote usage of drinking water from filters and piped water.

- iii.

Similarly, households consider the water obtained from wells as safe and do not adopt HWT. There is a dire need for a comprehensive study to be conducted in order to analyze the levels of pollution in the drinking water obtained from wells.

- iv.

As mentioned earlier, larger families do not adopt HWT, and they try to use those water sources where they can get a large quantity of water without any cost. Consequently, as a result, larger families obtain essential services at compromised quality. Policy makers must take appropriate measures to control population growth in Pakistan.

- v.

It is also recommended that policy makers in Pakistan take appropriate actions to empower women. Women's empowerment will not only uplift the conditions of women in Pakistan, but it will also have positive impacts on other social conventions including consumption of safe drinking water.

- vi.

The study also found that awareness created by media and education play a significant role in determining the consumption of safe drinking water in Pakistan. Therefore, it is suggested that the government, along with different NGOs working in the social sector, launch awareness campaigns regarding the hazards of consuming unsafe water and adoption of HWT. In this regard it is also recommended that issues associated with safe drinking water be included in the curriculum of public as well as private schools.

Data from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018 are available online. They can be accessed at https://www.nips.org.pk/study_detail.php?detail=MTgw (PDHS, 2018).

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

The author is extremely thankful to the referees and editors of this paper. Their valuable comments improved the paper to a great extent.

This paper was edited by Luuk Rietveld and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abrahams, N. A., Hubbell B. J., and Jordan J. L.: Joint Production and Averting Expenditure Measures of Willingness-to-pay: Do Water Expenditures Really Measure Avoidance Costs?, Am. J. Agr. Econ., 82, 427–437, 2000.

Akram, N.: Women Empowerment in Pakistan: its dimensions and determinants, Soc. Indic. Res., 140, 755–775, 2018.

Brick, T., Primrose, B., Chandrasekhar, R., Roy, S., and Muliyil, J.: Water Contamination in Urban South India: Household Storage Practices and their Implications for Water Safety and Enteric Infections, Int. J. Hyg. Envir. Heal., 207, 473–480, 2004.

Bruce, L. and Gnedenko, E.: Avoiding Health Risks from Drinking Water in Moscow: An Empirical Analysis, Environ. Dev. Econ.,4, 565–581, 1998.

Brown, J. and Clasen, T.: High adherence is necessary to realize health gains from water quality interventions, PLoS One, 7, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036735, 2012.

Checkley, W., Robert G. B., Epstein, L., Cabrera, L., Sterling, C., and Moulton, L.: Effect of Water and Sanitation on Childhood Health in a Poor Peruvian Peri-Urban Community, Lancet, 363, 112–118, 2004.

Clasen, T. F., Alexander, K. T., Sinclair, D., Boisson, S., Peletz, R., Chang, H. H., Majorin, F., and Cairncross, S.: Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhea, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004794.pub3, 2015.

Curry, E.: Water scarcity and the recognition of the human right to safe freshwater, Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights, 9, 103–121, 2010.

Cutler, D. and Miller, G.: The Role of Public Health Improvements in the Health Advances: The Twentieth-Century United States, Demography, 42, 1–22, 2005.

Daniel, D., Marks, S. J., Pande, S., and Rietveld, L.: Socio-environmental drivers of sustainable adoption of household water treatment in developing countries, npj Clean Water, 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-018-0012-z, 2018.

Daniel, D., Diener, A., Pande, S., Jansen, S., Marks, S., Meierhofer, R., Bhatta, M., and Rietveld, L.: Understanding the effect of socio-economic characteristics and psychosocial factors on household water treatment practices in rural Nepal using Bayesian Belief Networks, Int. J. Hyg. Envir. Heal., 222, 847–855, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.04.005, 2019.

Dasgupta, P.: Valuing Health Damages from Water Pollution in Urban Delhi, India: A Health Production Function Approach, Institute of Economic Growth, Working Paper Series No. E-210-2001, Delhi, India, 2001.

Fewtrell, L., Kaufmann, R., Kay, D., Enanoria, W., Haller, L., and Colford Jr., J.: Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Interventions to Reduce Diarrhoea in Less Developed Countries: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Lancet Infect. Dis., 5, 42–52, 2005.

Fotue, T. A. L., Sikod, F., and Abba, I.: Household choice of purifying drinking water in Cameroon, Environmental Management and Sustainable Development, 1, 101–115, 2012.

Haq, M., Mustafa, U., and Ahmad I.: Household's willingness-to-pay for safe drinking water: A case study of district Abbottabad, The Pakistan Development Review, 46, 1137–1150, 2007.

IHME: Global Burden of Disease Study 2015, available at: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (last access: 21 May 2019), 2015.

Jalan, J. and Somanathan, E.: The Importance of Being Informed: Experimental Evidence on Demand for Environmental Quality, J. Dev. Econ., 87, 14–28, 2008.

Jalan, J., Somanathan, E., and Chaudhuri, S.: Awareness and the Demand for Environmental Quality: Survey Evidence on Drinking Water in Urban India, Environ. Dev. Econ., 14, 665–692, 2009.

Jyotsna, J., Somanathan, E., and Choudhuri, S.: Awareness and Demand for Environmental Quality: Drinking Water in Urban India, South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics, Working PaperSeries No. 4-2003, Katmandu, Nepal, 2003.

McConnell, K. E. and Rosado, M. A.: Valuing Discrete Improvements in Drinking Water Quality through Revealed Preferences, Water Resour. Res., 36, 1575–1582, 2000.

Mintz, E., Rei, F., and Tauxe, R.: Safe Water Treatment and Storage in the Home: A Practical New Strategy to Prevent Waterborne Diseases, J. Amer. Med. Assoc., 273, 948–953, 1995.

Mintz, E., Bartram, J., Lochery, P., and Wegelin, M.: Not just a drop in the bucket: expanding access to point-of-use water treatment systems, Am. J. Public Health, 91, 1565–1570, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.10.1565, 2001.

PCRWR: PCRWR Biannual Report 2009-10, Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2012.

PDHS: Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18, National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS), Islamabad, Pakistan, available at: https://www.nips.org.pk/study_detail.php?detail=MTgw (last access: 16 November 2019), 2018.

Quick, R. E., Venczel, L. V., Mintz, E. D., Soleto, L., Aparicio, J., Gironaz, M., Hutwagner, L., Greene, K., Bopp, C., Maloney, K., Chavez, D., Sobsey, M., and Tauxe, R. V.: Diarrhoea Prevention in Bolivia through Point-of-Use Water Treatment and Safe Storage: a Promising New Strategy, Epidemiological Infect., 122, 83–90, 1999.

Rauf, S., Bakhsh, K., Hassan, S., Nadeem, A. M., and Kamran, M. A.: Determinants of a Household's Choice of Drinking Water Source in Punjab, Pakistan, Pol. J. Environ. Stud., 24, 2751–2754, 2015.

Sattar, A. and Ahmad E.: HHs Preferences for Safe Drinking Water, International Journal of Human Development, 3, 23–36, 2007.

Water Aid: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/The Water Gap State of Water report lr pages.pdf (last access: 12 March 2019), 2018.

WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme: Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000–2017, available at: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/jmp-2019-full-report.pdf, last access: 28 September 2019.

World Economic Forum: The global risks report 2019, 14th edn., available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2019 (last access: 23 September 2020), 2019.

Zulfiqar, H., Abbas, Q., Raza, A., and Ali, A. : Determinants of Safe Drinking Water in Pakistan: A Case Study of Faisalabad, Journal of Global Innovation in Agricultural and Social Sciences, 4, 40–45, 2016.